Use Preferences to change the theme

Theme:

Thank you!

Follow us:

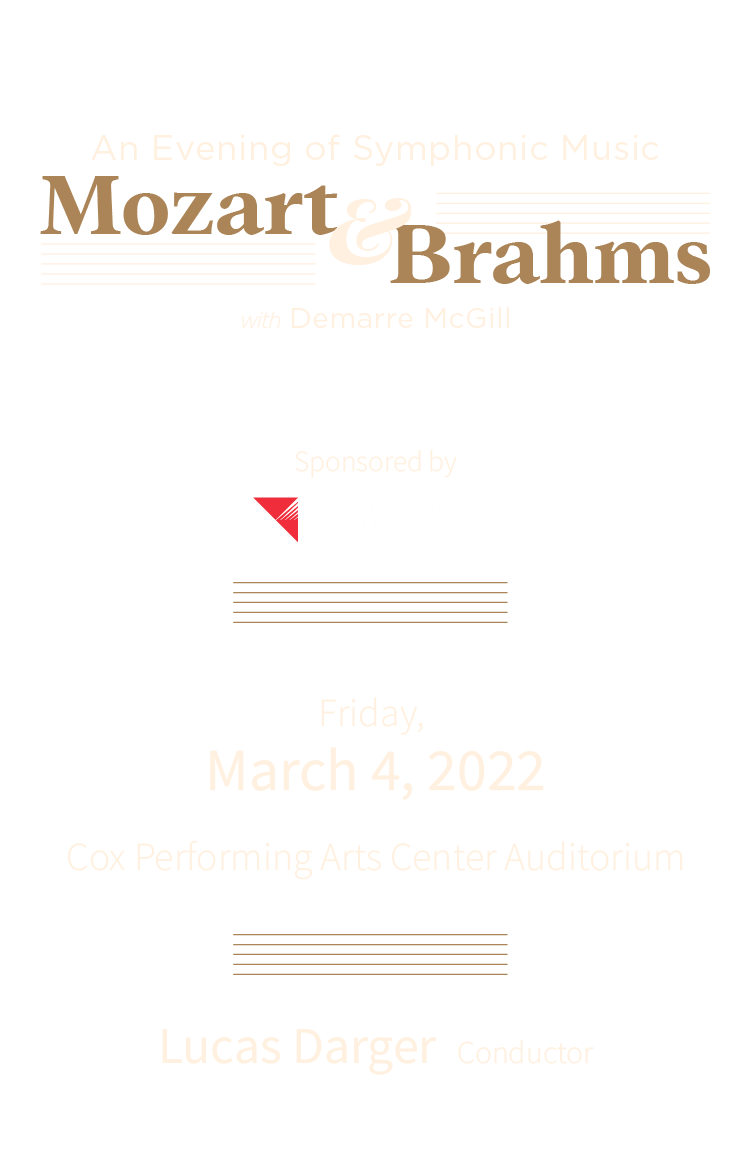

Tonight’s Program

Symphony No.1 in C Minor, Op.68

Johannes Brahms

I. Un poco sostenuto; Allegro

II. Andante sostenuto

III. Un poco allegretto e grazioso

IV. Adagio; Allegro

-Intermission-

.......

Flute Concerto No.1 in G Major, K.313

Demarre McGill, Flute

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

From the Board

Alyce Gardner

Board Chair

Dear Friends,

We are standing on the precipice of a new age. As we have painfully learned over the past months with Covid-19, our way of life has been threatened. We have experienced grief, loss, sadness and isolation. The performing arts have been stripped from our culture excluding us from the enrichment humanity desires and needs.

Moving forward, redefining an unknown future is as difficult as living through the changing realities of today. As we stand in this moment of reassessment it’s imperative we assimilate the lessons learned. How do we confidently move forward in this global state of affairs? I suggest we unite in a spirit of gratitude. Because of Covid, I have rediscovered a profound depth of appreciation for music and what it means to my way of life. To me, it’s not an accessory but an integral part of my life which makes me whole. Music and the arts are not recyclable assets I pull off the shelf when I need an emotional impact. They are part of me and define so much of who I am.

I hope we don’t lose sight of the lessons learned, but embrace a new way of living with a deeper sense of gratitude for the beauty in the world around us. Each day is a gift. Cherish this time. Enjoy living in each joyful moment and let the music inspire you like never before.

Meet the Maestro

Lucas Darger

Now in his sixth year with the Southwest Symphony, Maestro Darger is honored to continue to work with this amazing group of musicians and be part of this community. Under his leadership the symphony has continued to take on even more difficult repertoire each year and has risen to the challenge. The orchestra performs very diverse repertoire, from the masterworks of Beethoven to the hits of Billy Joel, and in April 2021 the orchestra recorded a special for national TV with Marie Osmond.

Darger is a passionate conductor and musician and strives to achieve expressive performances that captivate and energize audiences. He began his journey with conducting when he was sixteen years old after being asked to assist with the All City Children’s Orchestra. He continued to study conducting while pursuing a degree in Violin Performance, studying with Dr. Robert Baldwin and conducting the Lincoln Youth Symphony. He went on to earn a master’s degree in orchestral conducting from the University of Iowa. There he studied with William LaRue Jones and conducted both the Philharmonic Orchestra and the UI String Orchestra while performing with Orchestra Iowa and the Dubuque Symphony Orchestra. He completed further studies with Michael Jinbo at the Pierre Monteux School for Conductors before moving to Texas, where he joined the Valley Symphony Orchestra and conducted the South Texas Youth Symphony.

Special Guest

Demarre McGill

Flute

Winner of an Avery Fisher Career Grant and the Sphinx Medal of Excellence, Demarre McGill has appeared as soloist with numerous orchestras including the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Seattle, Pittsburgh, Dallas, San Diego and Baltimore Symphony Orchestras and, at age 15, the Chicago Symphony.

Demarre has participated in festivals around the globe, is co-founder of Art of Élan, a founding member of the Myriad Trio and, along with clarinetist Anthony McGill and pianist Michael McHale, founded the McGill/McHale Trio in 2014.

As an educator, he performs, coaches and presents master classes throughout the United States and in Europe, Asia and South Africa. Committed to teaching, he is on the faculty of the Aspen Music Festival and School, and holds the position of Associate Professor of Flute at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music,

Now principal flute of the Seattle Symphony, Demarre previously served as principal flute of the Dallas Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Florida Orchestra, and Santa Fe Opera Orchestra as well as acting principal flute of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

A native of Chicago, Demarre studied there with Susan Levitin, and continued his studies at The Curtis Institute of Music and The Juilliard School with Jeffrey Khaner and Julius Baker.

For further information, contact Miryam Yardumian at ACM 360 Artists 410-366-0911

Orchestra Members

Violin I

Rachel France, Concertmaster

Debbie Hafen, Assistant Concertmaster

Ahnalisse Gubler

Cari Jackson

Julia Monson

Amber Morris

Natalie Nelson

Cassidee Torres

Julie Valadez

Kimberly Warburton

Violin II

Joie Whittaker, Principal

Lichelle Jones, Assistant Principal

Camille Allton

Lauren Jess

Kristen Kjar

Andrea Luikart

Cyndi Martin

Melanie Nielsen

Debbie Thornton

Viola

Linda Ghidossi-DeLuca, Principal

Shay Manley, Assistant Principal

Craig Beagley

Norman Fawson

Kevin Lasnier

Dinah Nagel

April Olsen

Cello

Ka-Wai Yu, Principal

Peter Romney, Assistant Principal

Joe Duwel

Ann Evans

Sebastian Fraser

Leslie Jack

Peggy Lambert

Kent McDonald

Cameron Smith

Mia Taylor

Debra Vradenburg

Bass

Deni Jones, Principal

Ed Candland

Amy Gardner

Braxton Leavitt

Flute

Katrina Jones

Cassey Flinders

Oboe

Kendyl Johnson

Rhonda Rhodes

Clarinet

Melissa Bennion

Greg Johnston

Bassoon

Shanan Arslanian

Carolyn Johnston

Horn

David Hay

Randy Bassuener

Hannah Jeffs

Leslie Lintz

Trumpet

Jared Nicholson

Amy Paterson

Trombone

Tim Francis

Steve Davis

Jay Nygaard

Timpani

David Salisbury

Conductor

Lucas Darger

Music Librarian

Julia Monson

Tonight’s Pre-Show Music Provided by

The Youth Symphony Of Southern Utah

Youth Symphony of Southern Utah was founded in 2018 by Vista School in Ivins, Utah, and is an auditioned group for 9th-12th grade students in the St. George area. Students rehearse weekly and perform at many venues throughout the year. This group is directed by Linda Ghidossi-DeLuca, a Juilliard graduate and Teacher of the Year from the American String Teachers Association for the State of Utah. Students who participate in this group have the opportunity to play with other dedicated musicians who have chosen to make music a priority in their lives. The Youth Symphony of Southern Utah provides a rigorous and rewarding opportunity for all who are chosen to participate.

Program Notes

Symphony No.1, Op.68

Johannes Brahms, 1833-1897

The great nineteenth-century symphonic conductor, Hans von Bulow, reframed the well-known “three B’s” of the classical musical world to include the growing importance of Johannes Brahms. Throwing the rather disagreeable Hector Berlioz off the list, he immortalized Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. No new “Bs” have been added, so this is how the list has come down to us one hundred and fifty years later. Tonight’s concert features one of Johannes Brahms’ most important works for full orchestra. Unlike most first symphonies, Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 is not the work of a juvenile composer making their first big splash, but rather the mature product of a master composer that took fourteen years of constant revision and work to reach the concert hall.

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) was born in Hamburg to a musical family, with young Johannes receiving his initial musical training from his father, Johann Jakob Brahms. Johann Jakob could play any instrument at a professional level and made a comfortable living for his growing family, performing in multiple organizations around Hamburg. As his abilities grew, the younger Brahms showed great ability in his piano studies, causing his teacher to complain that he could be a major world performer if he would just “stop his never-ending composing”! His parents agreed. To make a living and support a family, paid performance with its guarantee of a steady income was much preferred to the tenuous world of trying to convince major performers to feature works for free!

Brahms’ piano abilities opened the door to meeting and working with the famed performers of the day including Ede Remenyi, Joseph Joachim, and Clara Schumann, which led to the eventual introduction to Robert Schumann. Networking is the word we use today, and Brahms could not be better networked to break into the front ranks of the composition world. As Brahms’ fame grew, publishing houses requested his music and he began to make money at the profession his parents initially discouraged. Brahms’ growing influence throughout the late 1850’s did suffer setbacks. Like any modern-day pop star knows, fame and approval and can be fickle, with poorly received works or performances leading to cancelled contracts and performances. Additionally, in 1860, Brahms was drawn into a public conflict with the always opinionated Richard Wagner. While an admirer of Wagner, he was not in favor of the bombastic style of Wagner and his operas. Wagner was the wrong guy to cross publicly and Brahms learned to stay out of the debates about which style is the “best”.

But talent will tell, and during the 1870’s, Brahms published works for every kind of musical ensemble, establishing his reputation beyond question. In expertise and interest, this wide variety of musical mediums resembled his long dead inspirations from the Baroque and Classical eras.

1876 begins the period of Brahms’ greatest fame, impact, and compositions as tonight’s First Symphony dates from this period. In character, Brahms was a perfectionist, deadly serious about getting his music as finely polished as it could be. This Symphony is Brahms’ 68th published work. Fourteen years of revision, experimentation, and restarting. The complexity of the work grew with Brahms’ growing sophistication. In style, his melodic and colorful use of the orchestra is decidedly Romantic era, but the underpinning of all music, how it is organized and put together, is an ode to the Classical and Baroque era, with the long-dead Beethoven resurrected in meticulous attention to form and key progression. Like composers of old, Brahms loved to create sophisticated counterpoint (two or more simultaneous melodies, blended to make a “whole”). You are getting the best of the past rejuvenated and revitalized with Romantic era melody and color.

The opening of the First Symphony demands our attention with a bold and dramatic statement from the full orchestra. The movement then uses the classic sonata-allegro form, with a theme, an elaborate development section, followed by a return to the original theme, to create structural unity. Brahms is the master of musical mood and he moves us through contrasting sections, keys and melodic material so the classical rigidity of the sonata allegro form is turned into a constantly evolving composition. The description of tempos, un poco sostenuto, allegroandmeno allegroare a forewarning of the variety of moods Brahms will use to engage us. The changes and evolution of harmonic and melodic ideas are both sophisticated and subtle, rendering a “play by play” description of this movement difficult. Words to describe the moods could include “tense, dramatic, mysterious, bold, lyrical, and energetic”, and all of these flow seamlessly together, blending into a unified whole. What began with such a bold opening evolves into a peaceful, quiet ending.

The second movement, andante sostenuto, shows Brahms’ ability to keep us constantly moving forward, one color and one idea evolving into another. Using the classical ternary form, or “song form” (A-B-A, with modifications) this movement features quiet, sensitive, lyrical moments in solo winds contrasted with flowing full string sections. As the movement evolves, new lyrical themes still have a spontaneous feel. With Brahms we are always going somewhere, albeit at Brahms’ pace, not ours. The movement ends with the same lyrical mood that it began with.

The third movement, un poco allegretto e grazioso, also follows the old A-B-A form…well, not really: Every time original themes return, they are modified and varied. Winds open this movement, with greater color and dynamic contrast than movement two, and with faster tempos and a more energetic feel. Still effortlessly flowing from one idea to the next, the graciousness and melodic beauty of the movement makes very clear the incorporation of the styles of the past with the styles of Brahms’ day. The short movement almost ends too soon.

The final movement’s description gives a hint of the great variety we will hear. Marked adagio, then piu andante, then allegro non troppo, then ma con brio, and finally piu allegro. These indicators are only a hint at the variety of changes we are going to experience. The introductory material is typical of the previous movements’ constant tonal and melodic evolution. At this point Brahms introduces one of the most famous melodic themes in classical music. With a clear theme statement, we feel we could almost hum along to this noble, lyrical line. But this is Brahms and he quickly creates ongoing variations of this famous theme. You will hear echoes and catches of the main theme throughout this section. The orchestra works to an energetic and heroic moment, as the theme returns again in the strings. The movement then creates another variation sequence of the theme, with snatches of the melody that modulate and grow in intensity. There are moments of imitative passages that echo back to Baroque traditions as the music creates more energy and complexity that evolve into dramatic and heroic grand statements as everything comes to a wonderfully satisfying climax.

“If we cannot write with the beauty of Mozart, let us at least try to write with his purity.”

-Johannes Brahms

Flute Concerto No.1 in G Major K.313

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart lived at a time of transition. The old world of nobility and rigid hierarchal classes was beginning to be challenged. A new belief of the importance of the common many was blowing towards Europe. The winter of 1777-78 saw a new American army survive the horrible times in Valley Forge and emerge to throw off British elitism and control to create an entirely new way to view people and their individual power. The old regime underpinnings of Western culture was being challenged with new political systems, new literary and music modes, and a new role for the common man. This was a time of change and contention, and Mozart moved the musical world in a new direction also.

Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was born in Salzburg, but like all famous musicians, he gravitated to Vienna, the musical center of Europe for decades. Brahms also moved to Vienna at the height of his career a hundred years later. Mozart’s early career as a child prodigy is well known, touring Europe with his father and making a name for himself wherever music was appreciated. Mozart’s early career looked a lot like the life of

professional musicians for hundreds of years. To make a living, you had to be hired by a rich court, endowed church or consortium of performance venues. But, the old patronage system, depending on born-to-power elites was beginning to crumble. Mozart was a leader in breaking this system, presenting and gaining economically from his own music as a composer. The break was not completed in Mozart’s day. While he was incredibly popular at all levels of society, the financial protections for artists had not evolved, so Mozart always had financial worries. This is maybe one historical fact the great dramatic play, Amadeus, got right.

It is hard to think of this Concerto being mature Mozart, but at 22 he had been composing and playing professionally for 18 years. One way a composer could make money was to write specific pieces for famous performers or patrons who would pay a one-time commission fee. The Flute Concerto No. 1 was commissioned in 1777 by the Dutchflautist, Ferdinand De Jean. These commissioned works were not usually performed in the large concert halls reserved for opera, but rather for more intimate settings or smaller halls. With no sound amplification, the size of the orchestra had to balance the single instrument, so ensembles tended to be small. Additionally, smaller orchestras were also a bit easier on the pocket books of the rich and famous. The piece is scored for a standard set of orchestral strings, two oboes, two flutes, and two horns. The three movements are as follows:

Movement 1 Allegro maestoso

One of the characteristics of the Classical era is the use of set forms to organize music. These are structures that guide the development of extended musical ideas so that there is a sense of symmetry with melodic material introduced, developed, and then a return to the original thematic ideas. In an era where the live performance is the only chance the listener gets to experience a composer’s art, the idea of repeating the important thematic material allows the “planting” melodic lines in our memory. This opening follows form. A delightful, upbeat melody introduces the flute entrance where Mozart seems to defy restrictive form. This is his gift for creating melody that simply delights. With the flute making the theme statement, there follows a section of development where melodic ideas are elaborated, explored, and taken into new keys further elaborated. Additionally, the flautist is given more and more technically engaging material, showing off their special talents. This culminates in an extended cadenza near the end of the movement where the soloist gets the opportunity to freely play with the melodic material showing off both musicality and technical ability.

Movement 2 adagio ma non troppo

The Brahms quote about Mozart cited earlier is seen most clearly in the beautiful simplicity of his slow movements. In an unusual move, Mozart brings two flutes into the instrumentation of the orchestra and it is these flutes that carry the initial melodic introduction. After the orchestral introduction, the soloist is almost “invited” to take the melody. Mozart adagio movements seem to always have a directed peace about them. The tempo and melody create a sense of beautiful calm, but the music is always moving forward. While the singing style of these movements may involve developing technical elaboration, this development is always driven by ornamenting the simple melodic theme. It’s not about the technical abilities of the soloist, but rather, the beauty of the melody.

Movement 3 Rondo: Tempo di Menuetto

A favorite form for Mozart final movements is the “rondo”. The rondo creates unity by introducing a main theme, then, after the initial theme statement an entirely new theme is introduced and explored. After that, there is a restatement of the original theme. In theme talk, it is A-B, A-C, A-D, etc. The contrasting themes allow fireworks and new material to be introduced, but always return to the original to create a unifying element. The tempo is usually much faster than earlier movements bringing a new kind of energy for the finale. Additionally, Mozart used the Minuet for its dance like lightness in a triple meter (three beat patterns) to contrast the feel of earlier movements. These movements allow the soloist to show off technique and provide lots of “fire” sections to further added technical excitement.